Is it really the “New York Review of Each Other’s Books”?

Measuring the extent of self-reviewing at the New York Review of Books from 1963-2022

(For Part 2, examining the changing demographics of NYRB contributors, click here.)

Since its 1963 founding, the New York Review of Books has been considered a bit clubby. Richard Hofstadter’s quip that it ought to be called the “New York Review of Each Other’s Books” is the most enduring line on the topic.1

Using metadata from all 59 years of the NYRB archives—spanning some 1,228 issues containing 17,268 articles about 31,579 books—I measured just how much of a “Review of Each Other’s Books” it has been.2

In short, my view is that Hofstadter was right. A hefty portion of the books reviewed in the NYRB have been contributors’ books. Furthermore, most of the contributors have had their own books reviewed.

But there are a number of different ways of adding the numbers up. Each says something slightly different about the intersection between contributors and the reviewed. I look at:

The proportion of reviews of books written by prior, recent and contemporaneous contributors

The proportion of articles written by contemporaneously-reviewed contributors

The relationship between the number of reviews a contributor has written and the chances the contributor has had a book reviewed

If you are not familiar with the NYRB, you should know it is a tabloid-sized magazine that comes out about every two weeks.3 Each issue features a series of longish reviews of mostly books and freestanding essays. What gets reviewed generally ranges from the highbrow4 to the upper-middlebrow.5 Instead of having a formal writing staff, the editors turn to outside contributors, some more frequently than others. Back in the early days of the magazine, its roster of writers read as a Who’s Who of New York Intellectuals.6

A Review of Each Other’s Books?

In the inaugural February 1963 issue of the NYRB, seven contributors both wrote reviews and had their own books reviewed, thus beginning a grand tradition at the magazine.7

Clearly, people contributing and getting reviewed in the same issue falls under the umbrella of a “Review of Each Other’s books, but how do you count it more broadly?

The low-hanging fruit here is the “each other’s books” part. You can look at each book that’s been reviewed and ask: Has the person who wrote this book contributed to the NYRB before?

By this measure, as of the April 21, 2022 issue, 27% of all NYRB book reviews have reviewed works by writers who had previously contributed to the magazine.8

In some 112 issues, half or more book reviews reviewed prior contributors’ books. In the most extreme example, all but one review in the February 16, 1995 issue featured a past contributor’s book. If you count letter writers as contributors (which I do not), every single review in that issue featured a past contributor’s book.

You can chart how this has changed over time.

Sort of predictably, the shape of this chart partly reflects the fact that the number of prior contributors grew over time. But it shows you that in some years you would find that as many as one in three reviews reviewed past contributors.

Still, this measure presents a problem of fairness. On the most basic level, does it really relate to the question of whether it's a “review of each other’s books” if some guy who wrote a review in 1963 had his book reviewed 25 years later?

The easiest thing you can do is simply say “let’s only count books written by people who contributed in the past year,” and you can substitute the past year part with a few different periods of time. Specifically:

six months (very recently)

one year (pretty recently)

two years (recently)

ten years (a while ago)

You can see that the numbers are lower—but not crazily so. You find that on average 20% of NYRB book reviews have reviewed the books of people who contributed in the ten years prior to the reviews, meanwhile the number only goes down to 10% when you limit yourself to looking at books by contributors of the past year.

There is still a slight problem with the years-before measures: excluding people who contributed soon after they got reviewed. For example, in the first issue of the NYRB Robert L. Heilbroner and Arthur Schlesinger Jr.’s books were reviewed. Heilbroner and Schlessinger then contributed to the second issue. We’re missing them in our counts, though I think you should count them.

This gets me to my third measure: contemporaneous reviewing. Instead of determining whether a book’s author contributed in the past year you ask: did the person who wrote this book contribute in the past year or will they contribute in the next year?

Since you’re looking at bands of time that are twice as wide, the numbers go up, but they don’t double. Instead they only go up by about 40%. You find that 27% of reviews review books of people who contributed within ten years of being reviewed—and 13% within one year of being reviewed.

Counting Contributors Who Get Reviewed

It’s also worth looking at the proportion of contributors at any time who get reviewed around the time they contribute. On some level you would expect this to mirror counting reviews of contributors’ books.9 But saying 19% of 2017’s contributors got reviewed in the year before they contributed is different from saying 10% of book reviews in 2017 reviewed books whose authors contributed in the past year.

Ultimately you find that in any given time about 14% of articles have been written by people who have their own books reviewed within six months of writing for the NYRB. That number goes up to 25% within a year and 40% within two years.

The mega metric: contributor-author overlap

I actually think it is the phenomenon of seeing the same names both reviewing and being reviewed at around the same time that creates the feeling that the NYRB is a “Review of Each Other’s Books.”

So to wrap things up I will use an all-inclusive measurement where you look at reviews of contributors’ books and articles by reviewed contributors together.

Specifically, I count articles where:

either a person whose book is being reviewed also contributed around the time of the review

or the author of the article had a book of their own reviewed around the time the article came out

This is a bit of a mouthful to restate, so from now on I will simply call this contributor-author overlap.

When we measure it, we get the following chart:

On average, one in five articles appearing in the NYRB have had contributor-author overlap within six months, while the proportion grows to one in two when you broaden your consideration to two years.10 This has fallen off precipitously since 2015.

On one hand, there has been no period where a majority of the reviewed and contributors overlapped very recently (i.e. within 6 months). On the other hand, it is also quite clear that there have been times when a reader of the NYRB would rightly have perceived that many of the people who wrote the articles were also getting reviewed and vice versa.

Further, the perception that NYRB has been a “review of each other’s books” is especially validated if you consider the data at issue-level, which is after all how the magazine is consumed. There have been 160 issues (about 1 in 7) in which 50% or more articles represented instances of contributor-author overlap in the one-year period. That goes up to 638 issues (1 in 2) when you look at the two-year period.

To wrap up this section, you might find it interesting to know that there have been 176 reviews in which a reviewer has reviewed a writer who reviewed them (1.3% of all reviews).

If You Contribute More than Once, They’ll Review You

If it’s not clear from the above, the NYRB likes to review its contributors.

As of April 2022, approximately 2,489 people have contributed to the NYRB. 60% of them have had their own books reviewed in the magazine. Meanwhile 71% of the 1,240 people who have written more than one review have had their own books reviewed.11

The chart below maps out this relationship. You can see how after a certain point (57 reviews or so), so few people have written that many reviews that the chart just moves with individual writers.

Conclusions

I spent a while trying to come up with a numerical threshold for what would prove that the New York Review of Books was a “Review of Each Other’s Books.” I ultimately gave up. But as I said at the outset, it seems more right with all the numbers in hand to say that Hoftstadter’s analysis was on the mark.12

It’s quite likely that there’s something obvious that I’ve missed about the foregoing procedure, so I welcome any and all feedback or suggestions.

See https://quoteinvestigator.com/2021/01/24/review/ for an investigation into who actually said it first.

See infra Methods.

You will also find a somewhat entertaining letters section in the back, wherein contributors are given space to eviscerate anyone who dares criticize their recently-published articles. (I exclude the authorship of letters from my analysis.) There is also an occasionally amusing personals section, most famously mocked by Woody Allen in Annie Hall.

e.g., monographs/translated poetry

e.g., popular histories/documentaries

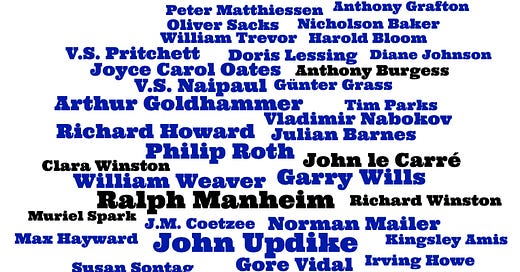

Those associated with the review still regularly invoke the names of early contributors in an epic cataloging that I like to call the enumeration. Quoth a NYRB advertisement:

“THIS IS THE PLACE WHERE: ISAIAH BERLIN wrote on Machiavelli - MARY McCARTHY reported on the Vietnam War - EDMUND WILSON attached Vladimir Nabokov’s translations of Pushkin, to which VLADIMIR NABOKOV replied - HANNAH ARENDT published her reflections on violence - I.F. STONE first investigated the lies of Watergate - SUSAN SONTAG challenged the claims of modern photography - ELIZABETH HARDWICK addressed the predicament of great women writers - MURRAY KEMPTON wrote on the Mafia - GORE VIDAL transported readers with a hilarious send-up of The New York Times bestseller list - V.S NAIPAUL… JOAN DIDION … GEORGE KENNAN ….”

To be clear, I actually quite like some of those writers and if they used to be part of something I was associated with, I would also regularly recite their names.

W.H. Auden, M.I. Finley, Paul Goodman, Dwight Macdonald, William Phillips, Philip Rahv, and Adrienne Rich.

More broadly speaking, 36% of NYRB reviews have reviewed works by people who ever contributed to the magazine.

Truistically, every time you find a review of a book by a contributor, there is at least one corresponding article written by the same contributor.

It is not a fair measure—as will be even clearer in the next section—but 87% of articles ever appearing in the NYRB were written by a contributor-author or reviewed an author-contributor.

It’s a bit less clean at specific review counts, but you find 46% of people who write only one article have had a book they wrote reviewed, 58% at two articles, 63% at three articles, and 72% at 5.

Or whoever actually said it first

Methods

To be very clear—since some of the people reading this are likely to be more book people than technical people—all of the heavy lifting that was involved in preparing the above numbers was done by computers. Specifically:

I wrote a script that went through the New York Review of Books Archives and collected information about every single article (but not letter) that has been published since 1963.

I used Beautiful Soup (a Python module) to extract key metadata about each article: who wrote it, when they wrote it, and what they reviewed.

I then organized information about all the articles in a giant table of sorts using another Python module called Pandas.

I then wrote functions that did things like cross referencing a contributor’s name with all authors who were reviewed between October 1, 1970 and October 1, 1972.

I opted to weigh everything by article. Where an article reviewed more than one book, and only one book met criteria such as being authored by a contributor, I counted that review. Attempting to weigh by the count of books reviewed raised a series of complications and invited deciding among compromises (i.e. should you discount a book when it is reviewed in tandem with four other books, should you count a review of ten books that meet criteria as having ten times as much significance as a standalone review of one book) (slight addendum 4/28—the numbers are also even higher if you do it by book count, so ). Weighing at an issue-level meanwhile, while actually more intuitive because it reflects how the NYRB is consumed, would lead in some instances to one article in a short issue having as much significance as three in a larger issue.

All date-relative measures were calculated to an article’s publication date, even though I opted to aggregate the data at the year level instead of using rolling averages. This is to say that if an article appeared in June 1970, if I counted one of the contributors as having been reviewed in the previous year, I looked at reviewed authors in the period from June 1969 to June 1970.

Further, as stated in the footnotes, I count someone as an author of a book if they have edited, introduced, or translated it. They have contributed to it in some substantive way if they get this top-line billing.