The New New York Review of Books

How tenured, diverse, male, and Ivy League have the contributors to New York's intellectual magazine been?

(For Part 1: Is it really the “New York Review of Each Other’s Books”?, click here.)

Russell Jacoby was unpersoned by the New York Review of Books. Admittedly, he first called the magazine stale.

In his 1987 book The Last Intellectuals, Jacoby argued the NYRB had started off “buzz[ing] with energy and excitement.“ It had gone wrong, he claimed, by largely turning to established professors to write articles, especially from the Ivy League, Oxford, and Cambridge instead of fostering new talent. “For a quarter century it withdrew from the cultural bank without making any investments,” he concluded.1

Before The Last Intellectuals was published, the NYRB had reviewed Jacoby’s books and sometimes mentioned him. Afterwards, he wrote in 2013, “I vanished entirely from the NYRB.” An editorial assistant told Jacoby at a party “that [his] name was mud over there and that [he] would not appear in its pages.” Jacoby conceded it was impossible to prove his blacklisting, yet admonished “memo to authors who speak truth to power: Do not speak truth to book-review editors.”2

At the risk of being unpersoned myself,3 in this article I conduct a statistical review of the NYRB’s contributors. Using 59 years of data from the NYRB archives—comprising 17,268 articles by 2,241 writers—I look at how the composition of this elect group has changed over time and evaluate some of Jacoby’s criticisms.

Specifically, I examine:

The onboarding of new talent, contributor tenure, and the generationality of contributors

The diversity of the contributor base

The gender distribution of contributors

The extent to which contributors are academics and teach at elite universities

I find that in recent years the makeup of the NYRB’s contributors has markedly changed. Articles are increasingly written by new contributors and article authorship is less concentrated among a few top writers. A far greater proportion of articles is also now written by women. I also find Jacoby’s assessments were somewhat right.

I wrap things up with a few fun charts about how book prices have changed over time, the proportion of articles that are actually book reviews, and top contributors.

Measuring New Blood

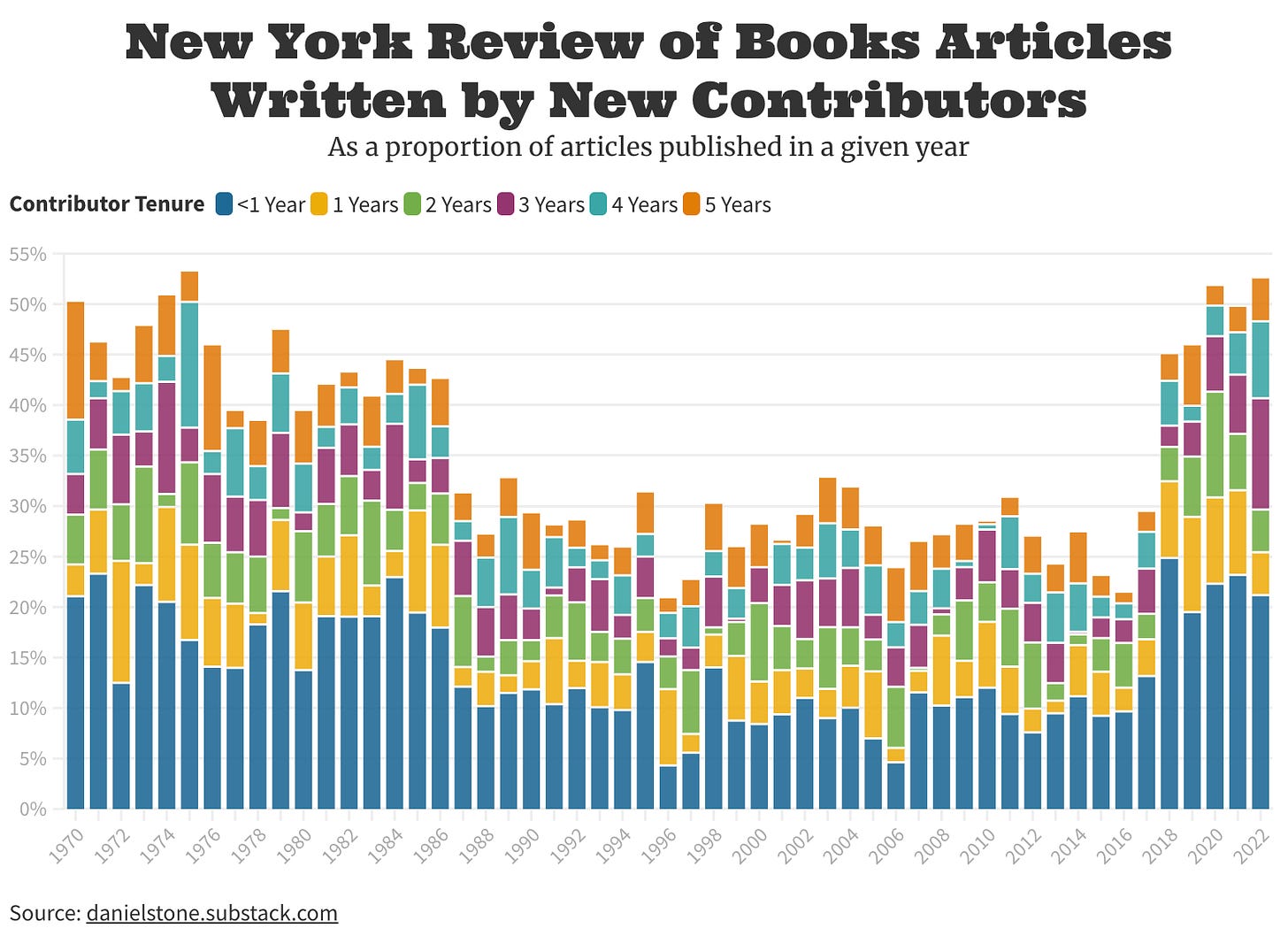

How well has the NYRB brought new writers into the fold? The most straightforward approach is looking at the proportion of articles written by new writers.

What most stands out is how, starting in 2017, the proportion of articles written by newer contributors surged. In 2020, for the first time since 1975, more than half of the articles appearing in the NYRB were written by newer writers.

You can also see that after 1986, the proportion of articles written by newer contributors sharply dropped off, neatly coinciding with the publication of The Last Intellectuals. Admittedly, Jacoby was also mostly commenting on the preceding decade, during which a much higher proportion of articles were written by new contributors.

Generationality

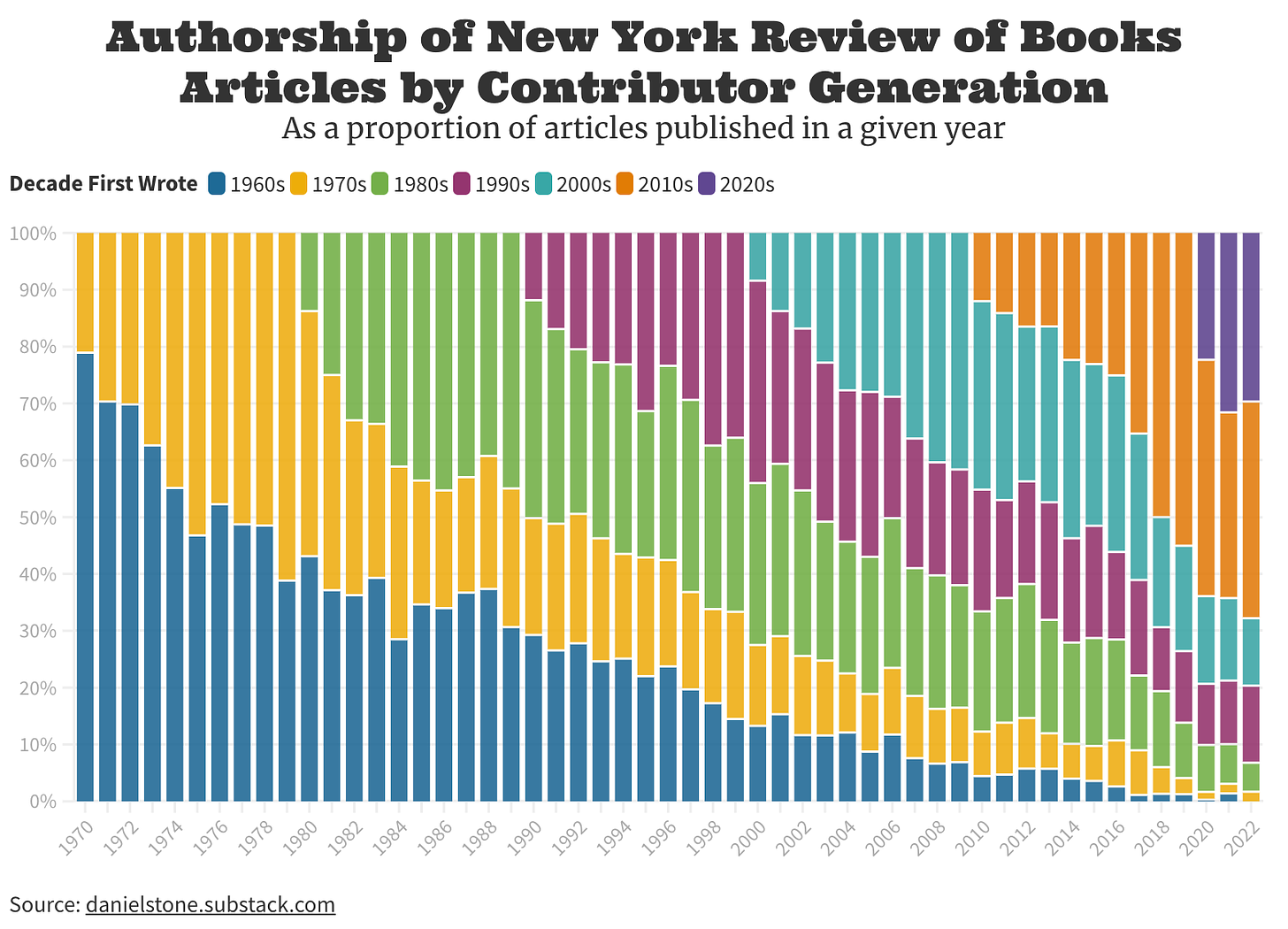

You can also group contributors by when they first wrote for the NYRB and then determine the proportion of the articles that each “generation” has written over time.

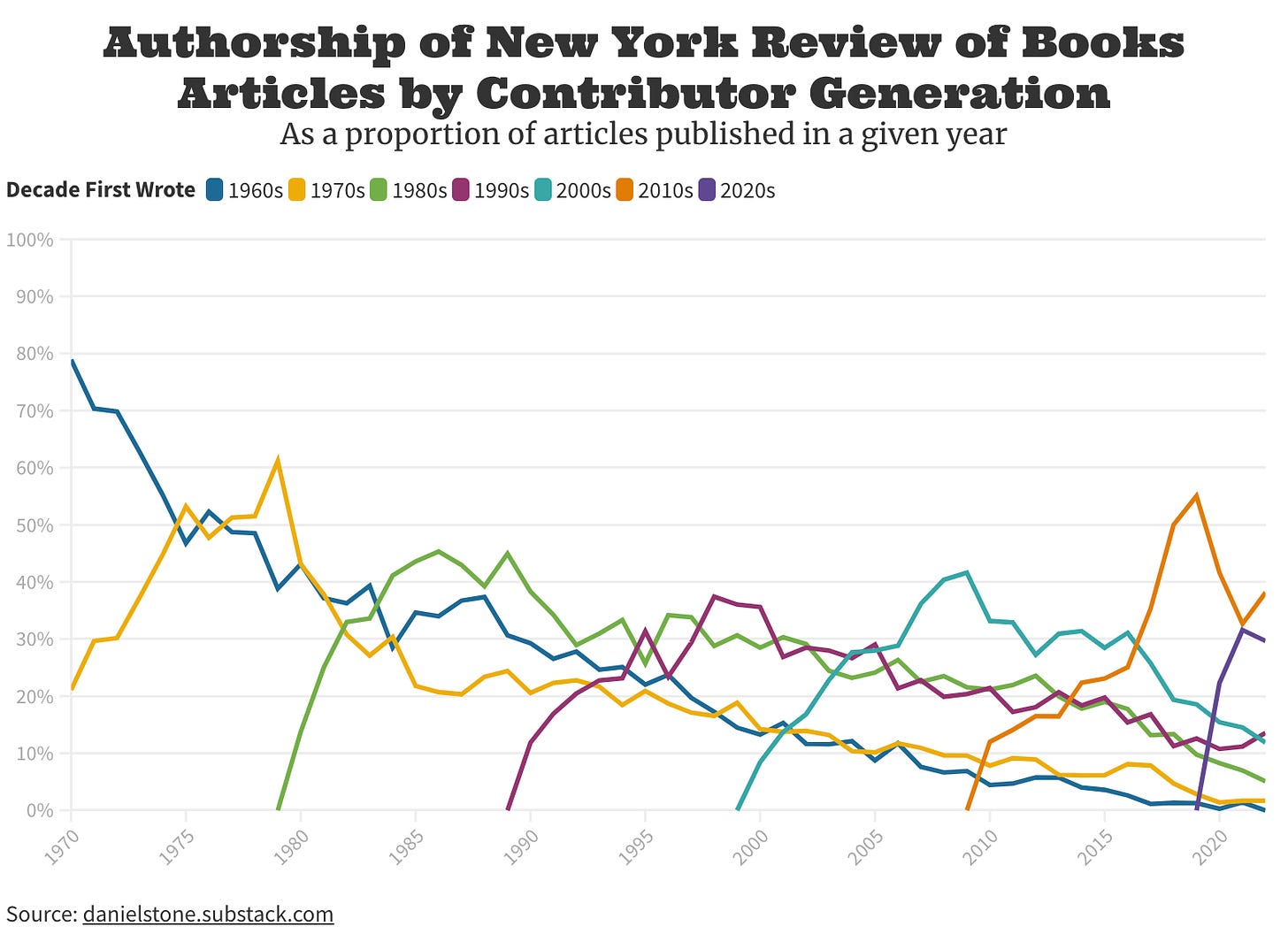

While it is a slightly less pretty, viewing this chart as a line graph better illustrates how generations of contributors overtake one another. Specifically you see that contributors who first wrote for the NYRB in the 1980s sustained their presence for longer than those of the 1970s and 1990s.

You can also see how the influx of contributors from the 2010s surpasses that of every preceding decade, except for the 1970s, when the only other generation of contributors were from the 1960s.

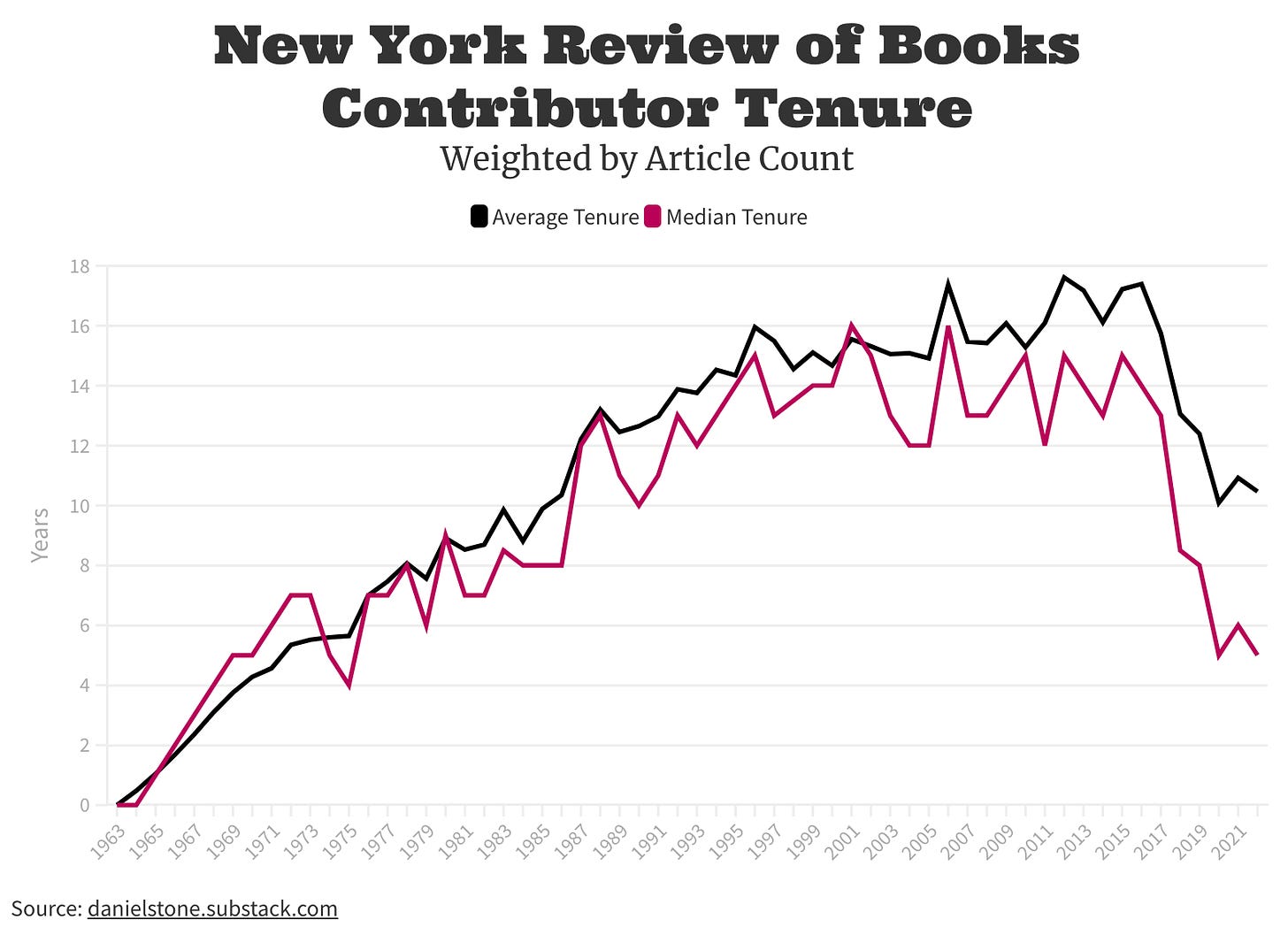

Tenure

Looking at the average and median tenure of contributors, you can see how it has correspondingly dropped in recent years.

The sharp drop in contributor tenure represents both the effective disappearance of the earliest generations (1960s/1970s) of contributors in recent years and how the newest contributors have leapfrogged contributors from the 1980s and 1990s in presence in the magazine.

In some ways the above charts are also proxies for actuarial charts. But it’s not purely that. These charts also show how at some points the NYRB welcomed and retained new writers more than it did at other times.

You might observe that from its 1963 founding until 2017, the NYRB was run by the same editors, Barbara Epstein (until 2006) and Robert Silvers—that most pronounced changes have happened since Silver’s 2017 death. Obviously the subsequent changes in leadership play some part in the influx of new writers.

Concentration in the Marketplace of Ideas

In the absence of formal staff writers, the NYRB’s editors have repeatedly turned to and handful of favored contributors. Any regular reader will note the frequent appearance of certain names. But how much has this group dominated the magazine’s pages?

In the world of antitrust, a measure called the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) is used to measure market concentration. You can also apply it to the authorship of NYRB articles. Specifically, you can invert the HHI to calculate the number of effective contributors in a given year. The higher it is, the more evenly NYRB article authorship is spread across contributors in a given year.

What the numbers show is that in recent years, writership has increasingly been spread more evenly across contributors, while in the 1970s a much smaller group of people did most of the writing.

You can also look at the proportion of articles written by top contributors. Over the entirety of the NYRB’s history the top 20% of contributors have written 77% of articles, but in a given year the top 20% of contributors has consistently written about 42% of articles. I think the second, smaller figure better reflects how the concentration of authorship actually works.

When it comes to these figures especially, I think imparting any value judgment would be wrong. You would not count having staff writers (which is what regular contributors effectively are) against a magazine. This is much more what I would call an attempt at trying to place the role of regular contributors.

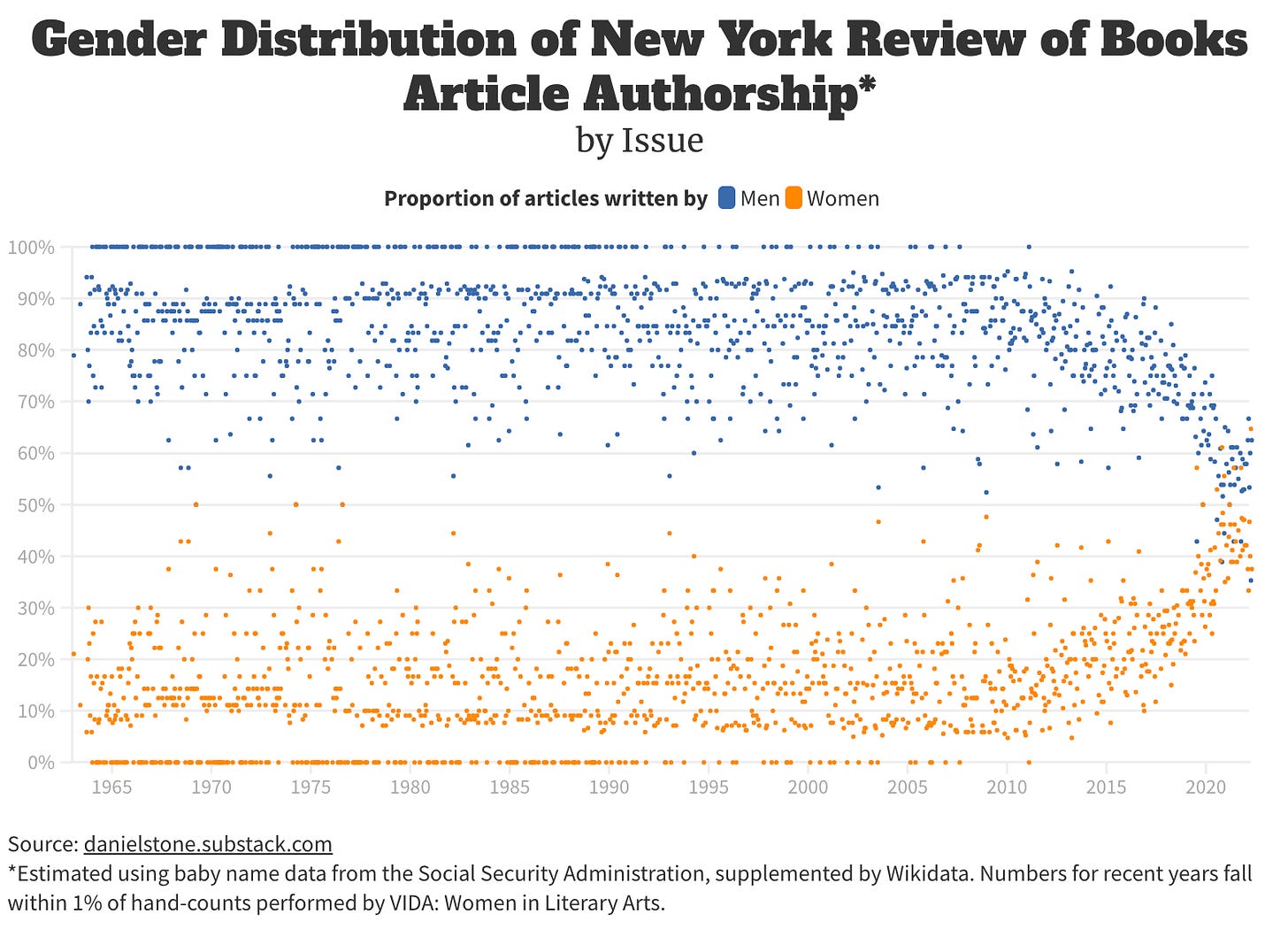

Gender Distribution

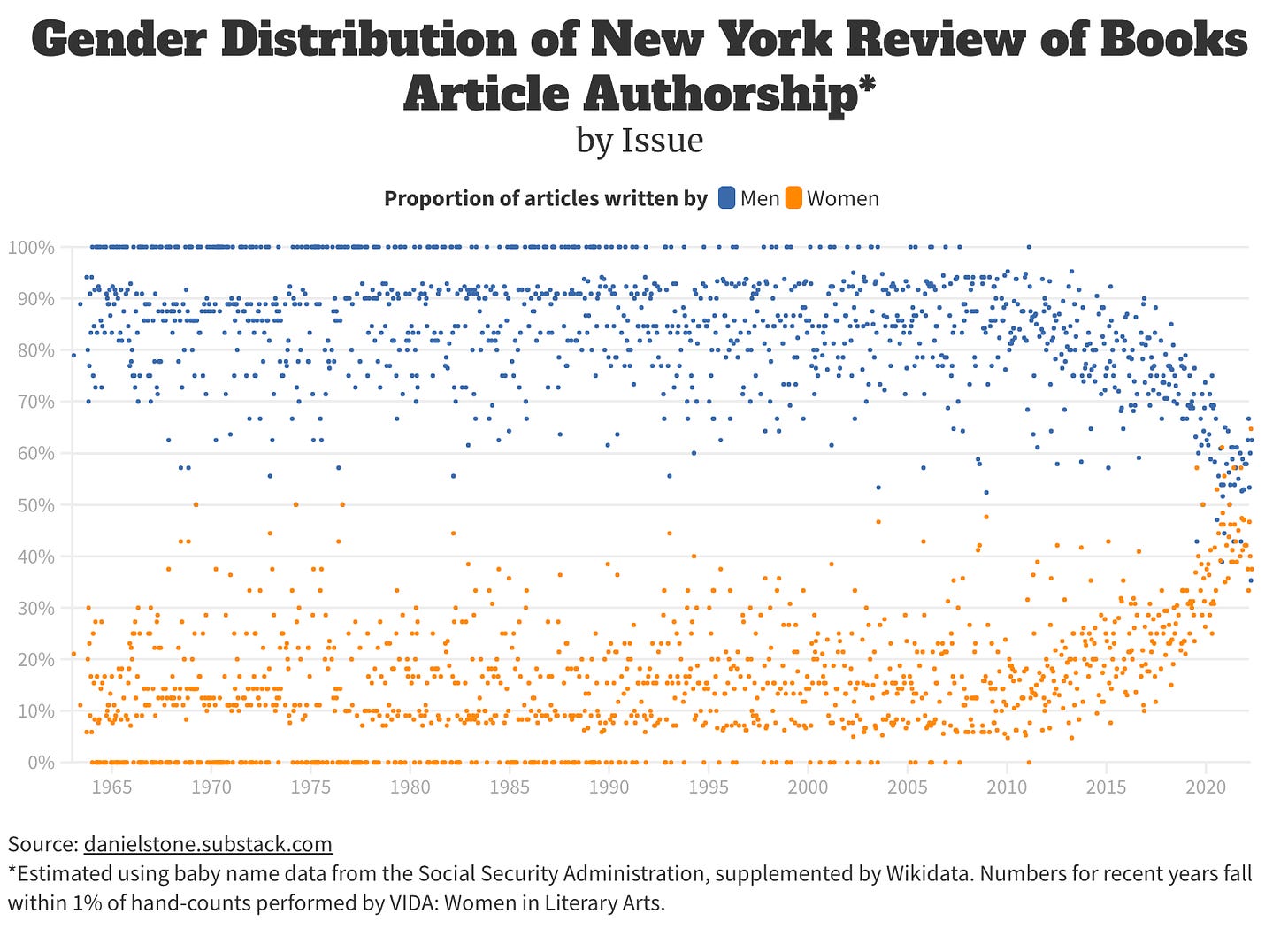

The single most startling trend I found when looking at the NYRB index is how the gender balance of contributors has changed over time. I coded for contributor gender using Social Security Administration baby name data and supplemented it using Wikidata.4 Very satisfyingly, my estimated counts fall within a percent of VIDA’s, an organization that conducts hand counts of the same numbers. In short, it has become a lot more even—though it still skews towards men.

Interestingly, upon her assumption of the NYRB’s editorship, Emily Greenhouse told the New York Times “addressing the reality reflected in the VIDA count [would] be part of her mission.”

It is also interesting to plot this on an issue-by-issue basis.

What you are seeing is that there are only twelve issues out of 1228 (1%) to which women have contributed half or more of the articles. Nine of them have appeared within the past three years. Meanwhile there are about 196 issues (16%) to which not a single woman contributed an article.

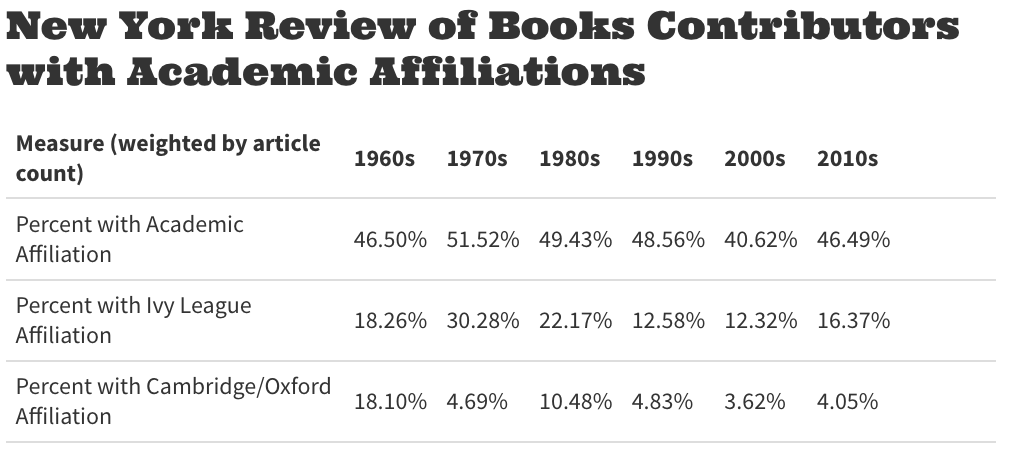

A Revolution of the Professoriate?

Lastly, I would like to turn to Jacoby’s position that the NYRB increasingly turned to professors to write articles. This is part of a wider and interesting theory he proposed that the universities started employing the people that used to be independent serious writers.

Because the NYRB prints blurb biographies of contributors, you can cross-reference them with keywords corresponding to teaching at universities (e.g. “professor”,”chair of”) and specific schools, while excluding erroneous false-positives (e.g. “Oxford History”,“University Press”). I caution that of all the metrics used in this article, these are the least robust.

You find that the NYRB has always drawn on academics, but that has drawn them from Ivy League and the Oxbridge schools to varying degrees.

Perhaps more clearly, you can tabulate these numbers by decade.

Jacoby was right in observing that the proportion of Ivy League contributors grew sharply after the first years of the NYRB. Otherwise, there are not many notable trends, other than the fact that the proportion contributors from the Oxbridge schools peaked in the early sixties, during an era in the magazine’s history Philip Nobile has termed the “London Review of Books” period.5

Conclusions

I must confess that reading Jacoby’s criticisms of the NYRB is what inspired me to start reading it in high school. The idea of a magazine that wasn’t an academic journal written largely by professors on general topics actually seemed quite appealing to me.

I’ll also admit to not regularly reading the NYRB anymore, largely because at some point in the last few years, the publisher cheaped out and started using a very thin material for covers, which made it inconvenient to throw in a backpack. So I can’t exactly comment on whether any of the trends discussed above have affected the quality of the writing.

What I will say, however, is that it’s quite clear that the handing off of the NYRB’s leadership in recent years has coincided with a large shift in who writes its articles. Anecdotally, among the new cohort of contributors are several young writers still in their twenties, whom I would count as loose acquaintances, the very sorts of people whose absence Jacoby lamented. Their presence of course does not necessarily spell a renaissance for the magazine, but it does suggest a willingness to open its doors to the unfamiliar.

Appendix: Fun Charts that Didn’t Fit

You can now view the charts at the post this sentence links to.

Edit (5/27): Moved top charts and other appendices to a separate post.

Russell Jacoby, The Last Intellectuals: American Culture In The Age Of Academe (1987), pp. 218-220.

Such tactics are not beneath the NYRB’s editors. A 2017 Times article described a longtime contributor experiencing “unanswered letters and phone calls … [making] it clear to her that her reporting from Washington was no longer wanted. Meanwhile an obituary of longtime editor Robert Silvers in Guardian states “At his most alarming, Silver [sic] could ‘unfriend’ (to use a term he wouldn’t have understood) a contributor, who would be bewilderingly dropped for years without explanation. Several contributing professors I contacted for comment said nicely that they would rather keep their contributing gigs than talk to a guy with a blog.

Highly unlikely given that I have never been personed by the NYRB. All my emails for comment have been ignored.

It’s a machine-readable version of Wikipedia. So for instance with V.S. Pritchett, who doesn’t have a first name like “Murray,” but who is well known enough to have a Wikipedia article, I could find a value with which to code him.

Philip Nobile, Intellectual Skywriting; Literary Politics & the New York Review of Books (1974), p. 31.