The story that won’t die

On the Financial Times claim that partners of Cravath, Swaine & Moore chant “The partner is dead, the firm lives” at firm funerals and the so-called “Cravath Walk”

Do partners of the esteemed law firm Cravath, Swaine & Moore recite a culty ritual chant at their colleagues’ funerals?

Yes, says an article that appeared in the Financial Times on April 9, 2018:

For those who stay the course to become Cravath partners, it is a lifetime career that comes with a guaranteed annual salary of several million dollars. Underscoring the “lifetime” part are traditions such as the Cravath Walk: every partner is entitled to a procession of past and present partners at their funeral, after which the assembled lawyers chant: “The partner is dead, the firm lives.”

It was an amusing side note in a story about firm compensation models written by James Fontanella-Khan, Sujeet Indap, and Barney Thompson, but the paragraph went semi-viral. I first read it the next day in Matt Levine’s popular Bloomberg newsletter Money Stuff. “It's like John Grisham meets Dan Brown,” he wrote.1

While it’s been nearly five years since the FT piece came out, the walk-chant story has remained in circulation—mainly because the idea of super-serious elite lawyers chanting about the immortality of their firm at funerals is absurd and really funny. The claim has in turn become part of Cravath’s reputational mythos—something I’ve heard retold a number of times when the firm’s name has come up at parties.2

Most recently, it exploded on Twitter in late December, when a screenshot of the FT paragraph posted by a “former lawyer” named Alex Su racked up nearly two million views. Su’s caption: “I can’t believe this is real.”

It turns out half the story is almost certainly real. A multitude of sources attest to the existence of the Cravath Walk, but only to the extent that it involves a procession of Cravath partners at firm members’ funerals.

As for any attendant chanting, there’s a lot less proof. The sole evidence appears to be the FT’s reporting—and the testimony of its reporters and publisher that they got their facts right, testimony that itself leaves room for doubt. Meanwhile, most of the record contradicts the claim.

This post is about why it’s unlikely that chanting happens at the funerals of Cravath partners.

The Incredibly Similar New Yorker Passage

The day the FT article came out, several people were quick to observe that the paragraph on the Cravath Walk closely resembled a passage in a wonderful 1993 New Yorker article by James B. Stewart about the murder of Cravath partner David Louis Schwartz:3

Marching two by two, uniformly clad in dark suits, ties, and white shirts, sixty partners of Cravath, Swaine & Moore marched slowly down the central aisle in a procession known as the Cravath walk—a tradition at the funeral of every Cravath partner. As they filled the front of the synagogue, their en-banc presence announced, as it had on so many occasions in the past, “A partner has died; the firm lives.”

Note that “A partner has died; the firm lives” is metaphoric, a literary turn of phrase; the “en-banc presence” of the partners personified—not the partners themselves—”announces” it. Yet twenty-five years later, in the FT article, we are told that a nearly-identical chant literally occurs.

To be specific about “nearly-identical,” merely three words—two if you don’t count a tense change—distinguish the figurative statement in the New Yorker article—“A partner has died; the firm lives”—from what the FT claimed is actually chanted—“The partner is dead, the firm lives.”

In face of the immense similarity between the two statements many people considered the matter settled: the FT had simply mangled the New Yorker's reporting.4

The resurfacing

Just like in 2018, when Su’s screenshot of the FT paragraph got retweeted thousands of times in December, the New Yorker article was speedily located—this time by Thomas Berry of the Cato Institute, who wrote, “I think the chant is a myth that began from misreading a passage from this 1993 New Yorker article, which characterized the *intended message* of the Cravath partners attending the funeral, as if it described them *actually chanting* the message.”

Su said “[v]ery interesting!” and retweeted Berry a few hours later, but the Tweet got only 58.7 thousand views—about three percent of what the initial tweet got.

The author of the New Yorker article disclaims knowledge of the chant

Perhaps more significantly, James B. Stewart (author of the New Yorker article) recently wrote to me saying that he had “never heard of any chanting.”5

The not-so-secret Walk

Since the 1993 New Yorker article was published, the Cravath Walk has been public, if perhaps somewhat obscure, knowledge.6 The Walk for instance has been referenced in the popular Vault Guide to the Top 100 Law Firms’ entry on the firm.7 Even Cravath itself is fairly open about the tradition, with partners acknowledging it on and off the record. Yet none have described the supposed chant and several deny its existence.

A very special firm

Cravath’s transparency about the Walk may be partly explained by the fact that the tradition’s existence is largely consistent with the highly prestigious8 and profitable9 firm’s ethos. It proudly and openly does things its own way—maintaining practices that stand athwart market trends.10

Notably, under the Cravath System, partners are promoted almost exclusively from within the firm’s associate ranks.11 Meanwhile, the firm does not hire associates laterally, but rather exclusively out of law school and clerkships. Partner compensation is largely based on seniority as opposed to the more widely practiced eat-what-you-kill model.12 It all seems to inspire a deep sense of firm identity. “A Cravath lawyer is what I am, not what I do” declares Evan Chesler, the firm’s former presiding partner, on a careers page.

For the select few who make the cut in the up-or-out system, Cravath partnership is an association for life. Retired partners eat lunch in the cafeteria,13 remain involved with firm affairs, and continue to be listed on the firm’s website. So the idea of partners attending the funerals of their colleagues together is not far-fetched at its face.14

Thus, in a May 1995 American Lawyer article that came on the heels of the New Yorker article, we read:

Two partners, who say they would like The Cravath Walk at their funerals, say they do think of Cravath as family. The Cravath Walk is done at the funeral of all Cravath partners, at the surviving spouse’s request. “It’s right that we should be right there with the family,” one partner says, defending the tradition.”

In the next paragraph, we get a bit more detail about the Walk:

Originally, the partners marched into the church (or, in recent decades, perhaps a synagogue) in “letterhead order,” as one partner explains, although that part of the ritual was eschewed for Schwartz’s funeral procession. As Stewart describes it in his article, it reveals something about the Cravath psyche: It is a visual statement, announcing, “A partner has died; the firm lives.” (emphasis added)15

Later, in 2017, Mark Greene, head of the firm’s Corporate Department went on the record with the FT itself about the practice.16

The firm and its partners deny the chanting claim

More recently, I emailed Cravath and a bunch of current and retired partners asking them about the Cravath Walk and whether it involves any chanting. They were surprisingly forthcoming.

Fallon Szczur, the firm’s Head of Communications, got back to me in a few hours with the following:

There is no such chant, nor has there ever been. Our partners attend services out of respect, and will enter and exit a service as a group (the reference to the “Cravath walk”) as a demonstration of collective honoring of their colleague if the family wishes that they do so.

Cravath Partner and former Southern District of New York judge Katherine Forrest, whose career at Cravath has spanned twenty-four years, remarked: “The one thing I can certainly say is that whoever came up with the chanting had a fanciful imagination; it is not true.”

Then, David Brownwood, who joined Cravath in 1968, was a partner from 1973 to 2003, and has since served as a Senior Counsel, wrote:

Many thanks for asking. The reports, like those of Mark Twain’s death while he still lived, are greatly exaggerated. It’s true that the family of a deceased partner or retired partner can request that the partners and retired partners who choose to attend his or her funeral or memorial service walk down the aisle after others are seated. In my 54 years at the Firm I’ve never heard, or heard of, a chant, or even an announcement from the officiant remotely like the quote. Some families choose not to request a walk.17

Where the FT and its reporters stand

In 2018, the FT reporters who wrote the story expressly denied that they had simply misread the 1993 New Yorker article.

When a commenter on the FT website alleged the reporting was wrong and taken from the New Yorker, Barney Thompson (a co-author of the FT piece) wrote: “Not so. We spoke to people inside and outside the firm who confirmed both the Cravath walk and the words (because they had been there).”

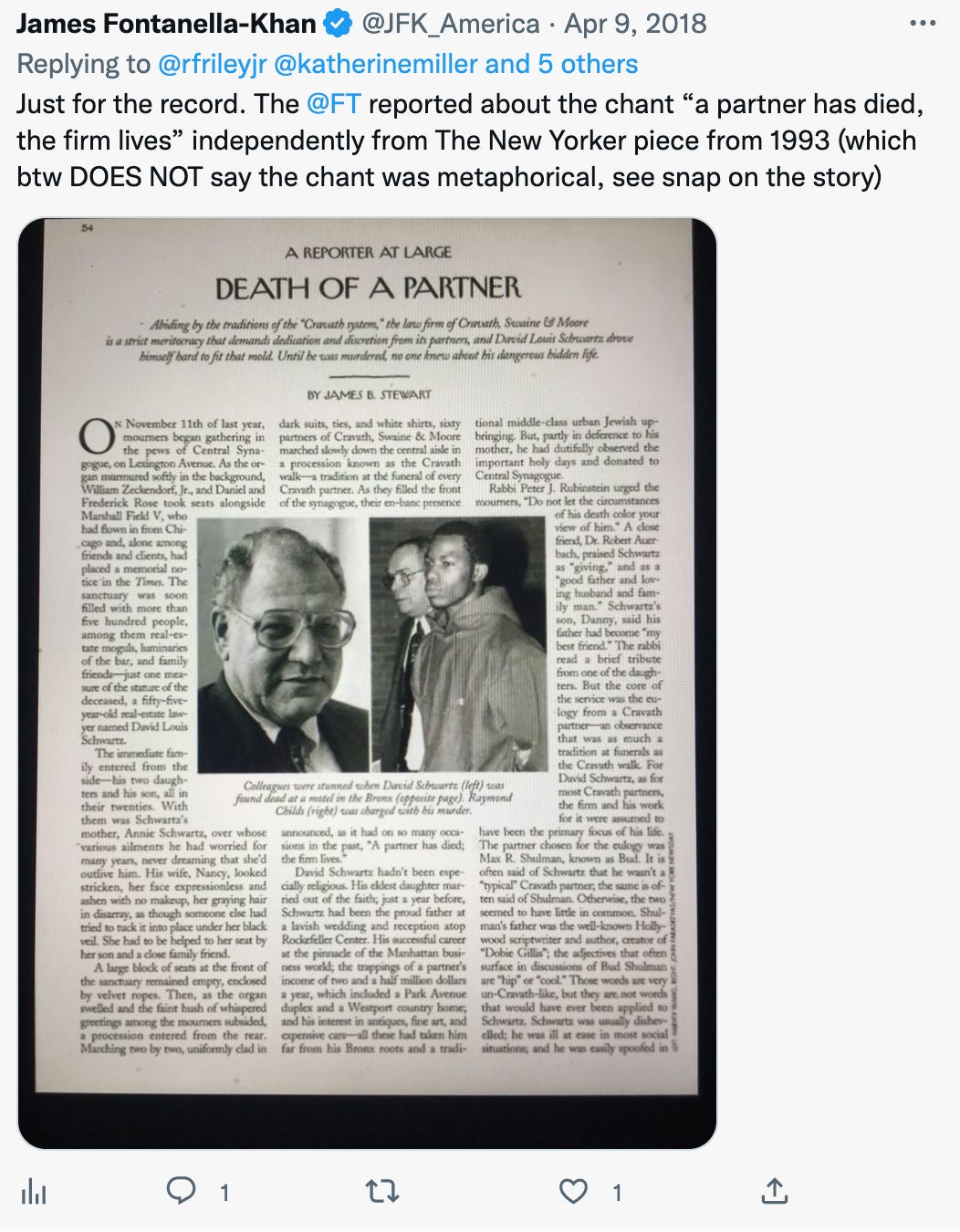

Meanwhile on Twitter, James Fontanella-Khan (another co-author of the FT piece) responded to a similar comment saying: “Just for the record. The @FT reported about the chant ‘a partner has died, the firm lives’ independently from the New Yorker piece from 1993 (which btw DOES NOT say the chant was metaphorical, see snap on the story).“

The original commenter replied: “(1) clearly the 1993 NYer story IS saying it figuratively and (2) large gaggle of partners from the whitest shoe firm of them all, sitting in pews at a funeral, literally chanting some lunatic slogan? Sorry, LOL.”

“Unfortunately you don’t know what you’re talking about. But your free to make up stuff. Take care,” Fontanella-Khan snapped back.

A More Tepid FT Denial

Today, the FT and the reporters who wrote the story are a bit less adamant about the veracity of the chanting claim.

After seeing the exploding tweet in late December, I initially emailed the reporters who wrote the 2018 story who are still at the FT purely out of curiosity about why there had never been a correction, and they kindly responded with more information.

When I asked whether I could quote their initial email in a post, Sujeet Indap (the only co-author of the FT piece from whom we have yet to hear) requested that I not, which I have decided to honor. He then added that “an obvious inference you can draw is that the FT has not received any request for correction or clarification and/or we stand by what we reported.” (Note the “or”.)

I proceeded to contact the FT’s communications team, who eventually got back to me with a somewhat terse official response, which was a bit more definitive, but said about the same thing. “The FT stands by its reporting. No complaint of inaccuracy was received for consideration by the FT,” they wrote.

Further, it would be unlikely that a correction would be appended to the article since there’s a time limit and they are issued: “Generally in circumstances where a complaint is received within 12 months of publication and it is shown that an article contains a significant factual inaccuracy.”

Even if Cravath issued a denial and complaint to the FT today: “the matter would be considered, but irrespective of any belated contentions raised, such a complaint might be rejected on the basis that it was not made within 12 months of publication.”

It’s worth noting that the New York Times has a bit less of a stringent statute-of-limitations approach to corrections. “Our goal is to correct things as soon as possible after confirming that a correction is warranted…. As far as timing, we generally correct articles within a year, but there are occasions when we've corrected older pieces. This one might be the most notable departure,” their communications team wrote to me, highlighting a 2014 correction to an article from 1853.

Asked about the sources it had relied upon, the FT said it had not relied solely upon the New Yorker’s reporting, but: “We don’t propose to reveal who our sources were but we can confirm we spoke with people with knowledge of the matter”—a bit less specific than the “people inside and outside the firm who confirmed both the Cravath walk and the words (because they had been there),” whom Barney Thompson claimed had verified the story.

Conclusions

Do the partners of Cravath, Swaine & Moore chant “The partner is dead, the firm lives” at the funerals of their colleagues as the FT claimed in 2018? I for one highly doubt it, however much I and many others might secretly want it to be true.

First and foremost, there is the fact that the supposedly chanted words are nearly identical to clearly figurative words that appeared in the New Yorker twenty-five years earlier.

Moreover, James B. Stewart, the author of the New Yorker article denies knowing about any chanting. Even if some sort of a chant exists, it seems unlikely that language he invented would end up becoming the go-to firm chant.

Mind you, Stewart—a Pulitzer prize-winning journalist—has written candidly about his time as an associate at Cravath and quite critically about his old firm. I strongly doubt he was involved in a chant coverup conspiracy—that in his serious and searching 1993 article, he decided to insert the words to a secret chant cloaked in metaphor as some sort of an inside joke for people in the know.

Then, there are Cravath’s denials. Admittedly, a more conspiratorially-minded person might say that of course the firm and its partners would deny that chanting takes place—that’s the most culty part. But the firm’s relative openness about the tradition of the Cravath Walk is at odds with that.

Lastly, the FT’s initial reporting and subsequent substantiation of the chanting claim leave something to be desired. It is not a small thing to say that the partners of one of the most venerable law firms in the country attend funerals—presumably surrounded by the family and friends of their deceased colleagues in mourning—and start chanting about the longevity of their firm. And yet this serious claim is made without any attribution—not even to some anonymous partner or attendee at a funeral.

While I think that the FT published a likely-erroneous bit of reporting in 2018, I strongly doubt that it did so intentionally. The three co-authors of the piece are serious reporters whose work I respect.18 I have no reason to doubt that they followed journalistically sound practices and confirmed the chanting claim with credible sources as they say they did. What I do think, however, is that it’s likely something got lost in translation in a game of journalistic telephone.

How did this happen? I think Fontanella-Khan and Thompson’s comments that immediately followed the publication of the FT story provide a fair amount of insight into how the story might have come about. Namely, Fontanella-Khan shared his view that the New Yorker article “DOES NOT say the chant was metaphorical,” which, as outlined above, is a disputable reading. Meanwhile, Thompson wrote about “confirm[ing]” “the words,” which does not necessarily suggest that the original source of the chant story was anything other than the New Yorker article. In combination—the misreading and perhaps an unclear request for confirmation of the New Yorker’s 1993 reporting—explain how the FT’s chant could have ended up so closely mirroring the New Yorker article’s metaphorical dirge.

I suppose the only way to truly verify the claim would be to attend the funeral of a Cravath partner whose family elected to have a Cravath Walk and hover around the partners, but that would be in rather poor taste.19

To be more complete, Levine (in his 10:27 a.m. newsletter) labeled the paragraph “some claims” and remarked:

"Entitled"? Would you ... want ... that? You'd be dead, of course, so you wouldn't care, but why would the families allow it? "Next up in the service: Harry's work buddies are gonna chant ominously for a while." It's like John Grisham meets Dan Brown. I hope they wear hooded robes for their chant.

Perhaps I am going to the wrong parties. More interestingly, nearly every time a Cravath lawyer (or summer associate or clerk) has been present while this has come up, they’ve cited the New Yorker article discussed below.

I really think it’s a great article; I’m happy to send anyone a copy. In one part of the story, Stewart goes on to highlight the somewhat-inappropriate nature of the outsized role Cravath partners played at the funeral relative to the other mourners:

But the core of the service was the eulogy from a Cravath partner—an observance that was as much a tradition at funerals as the Cravath walk. For David Schwartz, as for most Cravath partners, the firm and his work for it were assumed to have been the primary focus of his life.

“FT writer just did a bad job of taking notes on an old New Yorker piece,” wrote Ted Frank of the Hamilton Lincoln Law Institute. “[H]ahahaha that is quite a misreading,” wrote Matt Levine. “Looks like the author of this piece *might* have misread this earlier @NewYorker essay that mentions the Cravath Walk. It uses the phrase but doesn’t say that partners chant it aloud,” wrote Robert Tsai of Boston University Law School.

He added that he would need to check the story with his sources, but never got back to me.

Though the earliest reference to the Cravath Walk I could find actually appears in a 1980 National Law Journal article (“Wall Street’s True Blue Chip” by David Margolick) that was quoted in the Stanford Law Review in 1985:

Some years ago, mourners at the funeral of a Cravath, Swaine & Moore senior partner were treated to a singular spectacle.

Thirty five Cravath Swaine partners, all honorary pallbearers, marched down the aisle for their fallen comrade in a solemn procession, two-by-two, in precisely the order their names appeared on the firm's letterhead.

For instance, the 2000 edition’s section on the Cravath walk reads:

Cravath legend has it that when a partner dies, every other partner attends the funeral, forming a two-by-two procession called “the Cravath Walk." The practice arose in the 1950s when a number of Cravath partners died within a very short period of time, and the surviving partnership marched to demonstrate that the firm would continue despite the tremendous loss. “It’s right that we should be right there with the family," one partner once noted to The American Lawyer. Today, the procession takes place only if the surviving spouse requests it.

Somewhat amusingly, the firm published a press release to announce that it had been named the most prestigious law firm in the country by Vault in June 2022.

The Law.com 2022 ranking of profits per equity partner ranks Cravath seventh at $5.8 million per partner. (I think this is the same as the Am Law 100.)

A 2012 New York Times article about the hiring of former Antitrust Division head Christine Varney noted “she was just the fourth outside partner in a half century.”

Though it appears that about a year ago, they ditched the solely-seniority lockstep model.

As told to me by a former Cravath associate, who then remarked, “it’s as if they didn’t know where else to go.”

In fact, I was immediately reminded of an episode from Louis Auchincloss’s 1956 novel The Great World and Timothy Colt. Timothy Colt, an associate at a venerable New York law firm, is called upon by Mr. Dale the senior partner to arrange the funeral of a partner—Mr. Knox—and must explain it to his wife:

“Dale wants me to help with the funeral,” he said.

“It’ll be small, of course. Mrs. Knox wouldn’t want a big funeral.”

“But Dale does.”

“Dale! What does he have to do with it?”

“He simply happens to be the senior partner now,” he said wearily. “A man like Knox doesn’t belong only to his family. He’s a public figure.”

“You’re talking like Dale already!” she cried. “Darling, don’t!”

And later at the funeral:

Someone was at his elbow. “Mrs. Knox and the girls are coming in in a second. I’m joining the partners in their pew now. I haven’t seen Judge Lanahan, but if you spot him, for God’s sake see he goes up front.” (Emphasis mine)

In another paragraph of the somewhat wacky but great article entitled “Brand Names at the Brink” contemplating how you would weigh Cravath, Sullivan & Cromwell, and Davis Polk against one another if they went public, a Sullivan & Cromwell partner responds to the New Yorker article:

As one Sullivan & Cromwell partner puts it, James Stewart's disturbing depiction in The New Yorker of the funeral of murdered Cravath partner David Schwartz gave him the shivers. Not, as you would expect, because of the tragedy and horror of the event, but because of “The Cravath Walk”— the solemn procession of Cravath partners walking two by two into their partner’s funeral. “It was like something out of Woody Allen!” this S&C partner gasps. “The thought of something * like that—all Sullivan & Cromwell partners— at my funeral is horrifying. This place is not a substitute for your family.”

A friend of mine called this a “cope.” (Thanks to the New York Public Library for scanning the microfilm!)

The relevant section reads:

Whenever a partner or retired partner of Cravath, Swaine & Moore dies, the 198-year-old US law firm offers the bereaved family a “Cravath walk”. This involves the retired and active partners marching at the funeral, two-by-two, in age order — oldest lawyer to youngest.

I heard about the “Cravath walk” last week. Mark Greene, head of the firm’s corporate department and of its international practice, told me that the most recent walk had taken place at a memorial service about a month ago for a lawyer who had died at the age of 43.

I have made the two following light edits: I changed “Mark Twain’a” to “Mark Twain’s” and “I’ve never heard., or heard of, a chant, or even” to “ I’ve never heard, or heard of, a chant, or even”

For instance Indap’s book on the Caesars Palace LBO and bankruptcy—The Caesars Palace Coup— (co-authored with Max Frumes) is excellent, and I highly recommend it. Sort of a Barbarians at the Gate 2.0.

Though of course in the Curb Your Enthusiasm version of my life, we cut to thirty years from now, when I’m attending the funeral of a Cravath partner. As the partners file into the pew in front of me, I hear them murmur “The partner is dead, the firm lives,” and realize I was bamboozled.

tens of thousands of people attended these things over the years—throw a rock on Park Ave & you’ll hit one. and yet no one can be found who remembers strange chanting? get serious

"3 I really think it’s a great article; I’m happy to send anyone a copy."

Thanks. Please send me a copy.